tombé par hasard sur cette longue et détaillée chronique sur un blog ricain :

http://www.savagecritic.com/reviews/old-english-3/This is a softcover book from 1978, perfect bound and b&w and 64 pages for your post-bicentennial $4.95.

It’s big, as in “big as Paul Pope’s old oversized books, like Buzz Buzz Comics Magazine or THB Circus,” or almost as big as that new Seth book, George Sprott (1894-1975), or that recent hardcover he designed, The Collected Doug Wright. You know, the one with the infernally gleaming red cover? Hold that thing up to an adequate light source and you can transform an ordinary bathroom into a scene from Flashdance. Of course, that’s how my bathroom is already, but, like Seth, I’m an old-timey kinda guy.

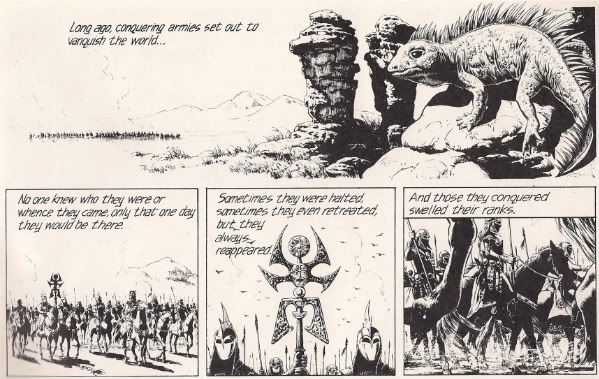

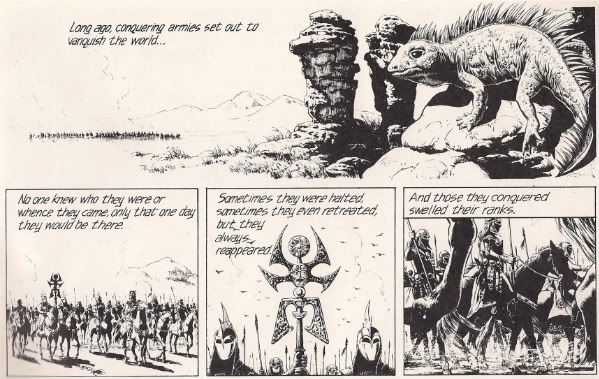

To wit: 1978, big ol’ softcover comic, big like the European albums, big in a way that seemed right for A Heavy Metal Book, just as they were new and hot, and the likes of Moebius’ Is Man Good? and Lob & Pichard’s Ulysses rolled off the presses. The world indeed seemed ripe for conquest, but this lost tome proved cautionary in more than its mere eventual obscurity. Battlefields may seem huge, barks the metaphor, but conquerors are thus necessarily small.

Conquering Armies is a suite of five short comics first seen in the pages of Métal Hurlant, and quickly brought to English via early issues of Heavy Metal. Obviously a lot of people believed in these stories, which weren’t lacking in pedigree: the writer was Jean-Pierre Dionnet, Hurlant’s co-founder and editor-in-chief, working with an artist he’d known for nearly his entire comics writing career, Jean-Claude Gal.

Granted, Dionnet’s comics writing career had only just started in ’71, with Gal following a year later, both teamed in the pages of the venerable Pilote, the growing pains of which would give way to Howling Metal just a few years later. Fast times, sure, but those virginal pages of 1975 looked like they had something to prove.

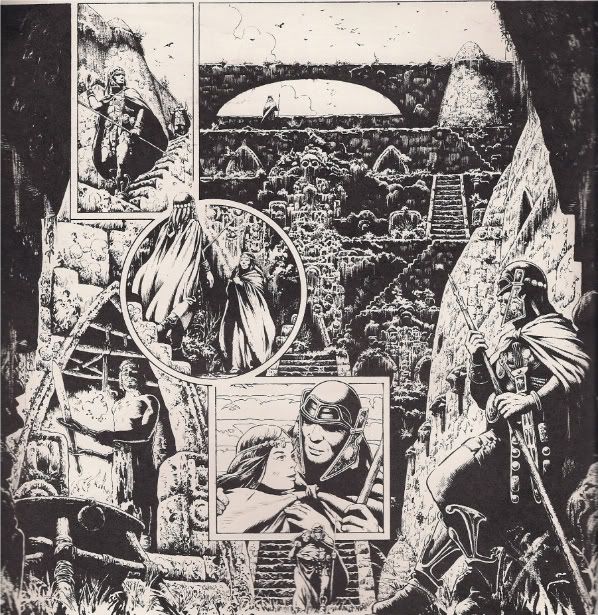

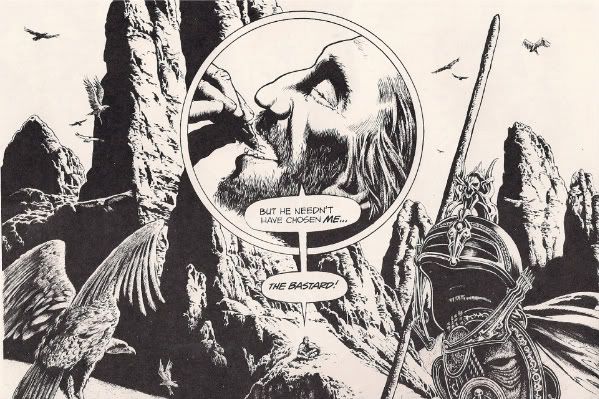

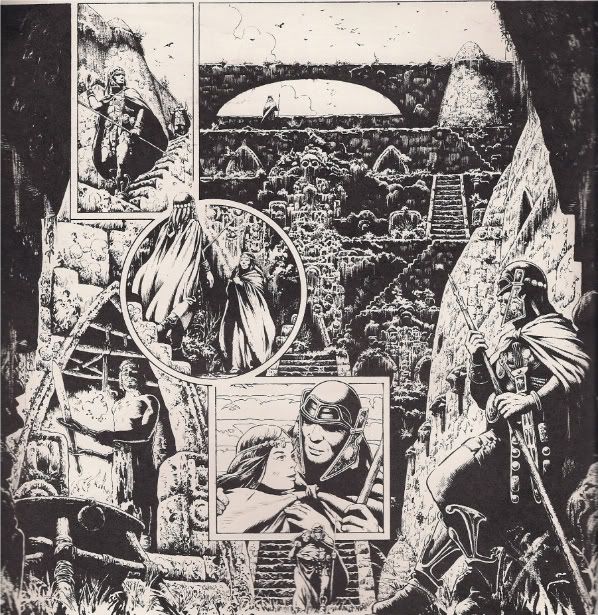

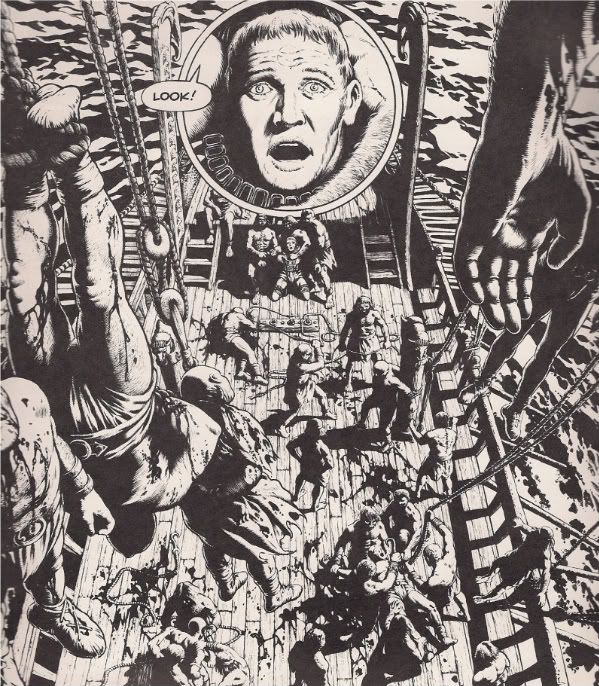

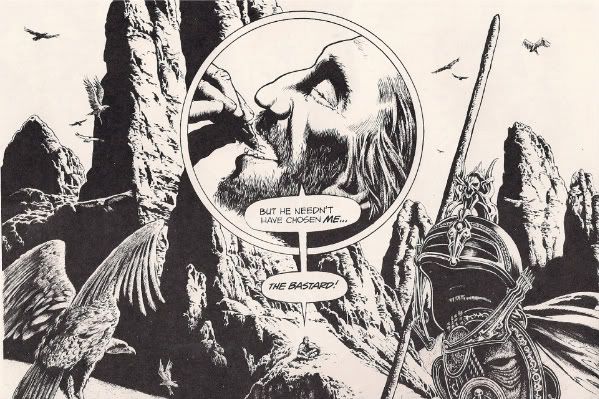

This is just a detail, mind you, as is every individual image in this post. You should see it in person. The stuff looks big in magazine form, but once you’ve witnessed those collected dimensions — which I presume match a ’77 French album of the same material — you’ll never settle for less. Gal wants to assault you with scope, much in the way he intimates violence toward those tiny soldiers, toy-like against their rocky scene so that magnified panels are necessary to track a man down the stairs, only then humanized.

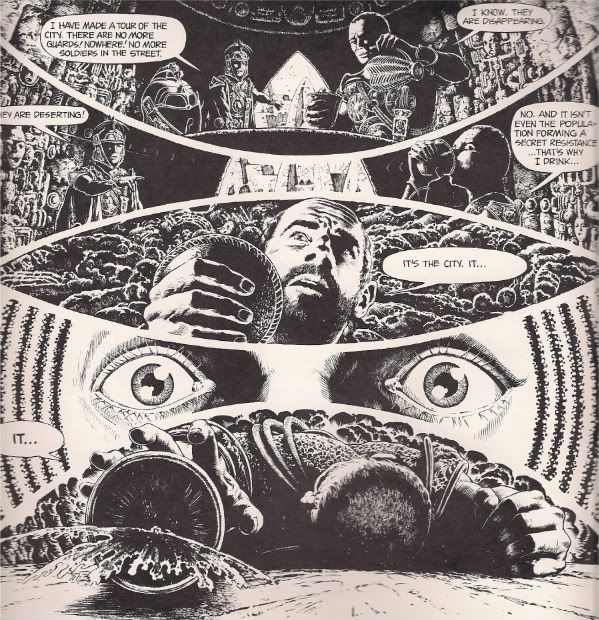

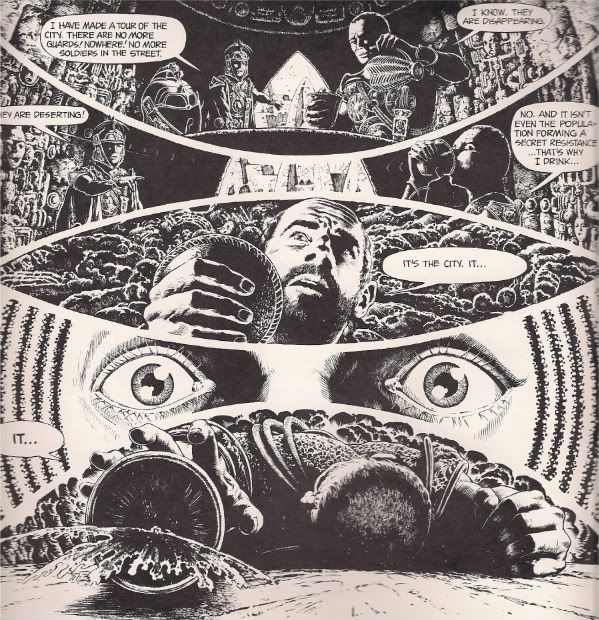

And that’s no basic establishing vista you’re seeing; the grandeur of Gal’s scenes is the very heart of this work, these linked stories, all of which seek to smother the ambitions of armies in the magnitude of greater existence. The first tale even stretches to literalize this notion, with a mighty vanguard rushing into a massive city that exacts a terrible psychological toll on the men, particularly as folks begin vanishing or falling over.

Heavy realism, that, at least in terms of character art. But Gal still emphasizes the scale of the room with his wide panels, pivoting to stretch the gulf between the characters and then zooming in to associate space with death. There’s a tremendous amount of detail in these panels, but it never becomes overwhelming until Gal wants it to, as a means of aggravating the story’s dread. When there comes a time when no detail at all would be better, the opportunity is taken.

All of this comes from a man three years into his professional comics career, although he’d been a drawing instructor for years prior. Yet remarkably little of the work suffers from the ‘frozen’ feeling illustrators sometimes bring to comics, or the sedate atmosphere of some older French adventure comics in a realist style, and I think much of that is due to the almost despairing sense of diminution Gal foists on his mighty warriors.

It’s very different from the world-building majesty of Philippe Druillet and his mad architectures and psychedelic combats – Gal is drawing ‘real’ people, and his real, big places are going to kill them, or at least foreshadow their doom via the looming presence of matters greater than martial accomplishment.

Very little of Dionnet’s comics writing has been translated to English, but what I’ve seen places him firmly in the political area of Hurlant’s approach to fantasy. There are no wild visions in here (or the Enki Bilal-drawn Exterminator 17) devoid of evident purpose, all of it rueful in facing the human condition.

All of the military adventures in this book are doomed, always by something out of the control of the powerful, be it chance or disease or magic. Or metaphor. There is no explanation as to why the city in the first tale destroys the occupying force; the men of violence merely vanish as we see them growing humanized, chatting with locals or abandoning their posts, worn down by time and seemingly absorbed by the enormity of Gal’s scenery. It’s not sorcery, really, but the symbolism of the huge city as the endeavor of occupation, or colonization, beating the materialism of combat by just sitting around it.

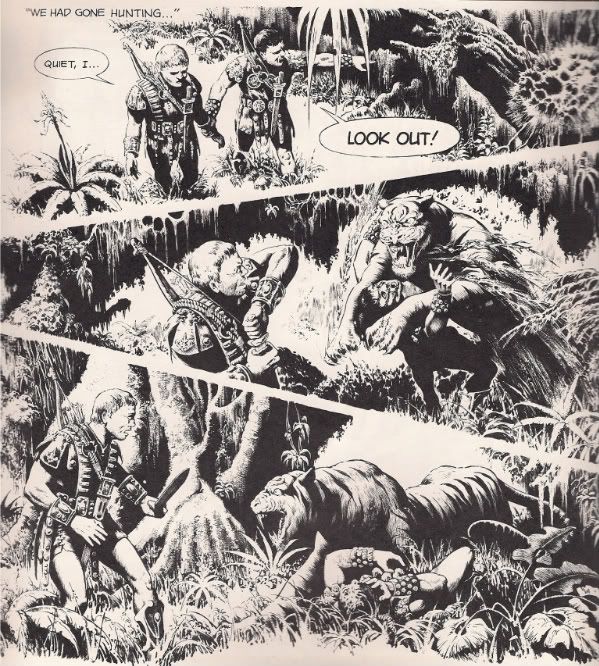

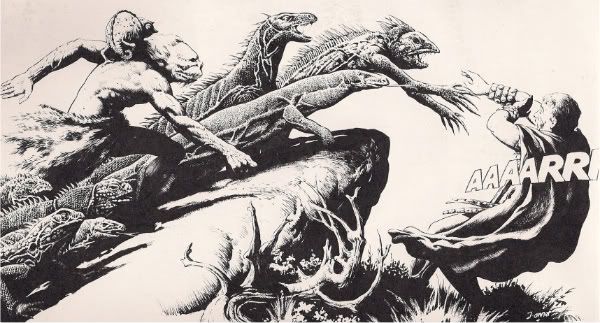

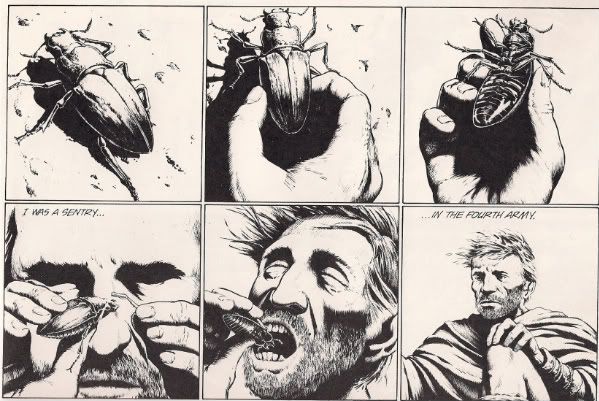

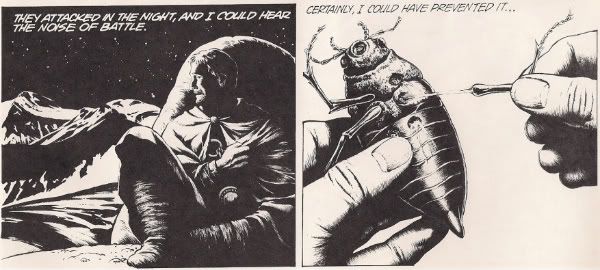

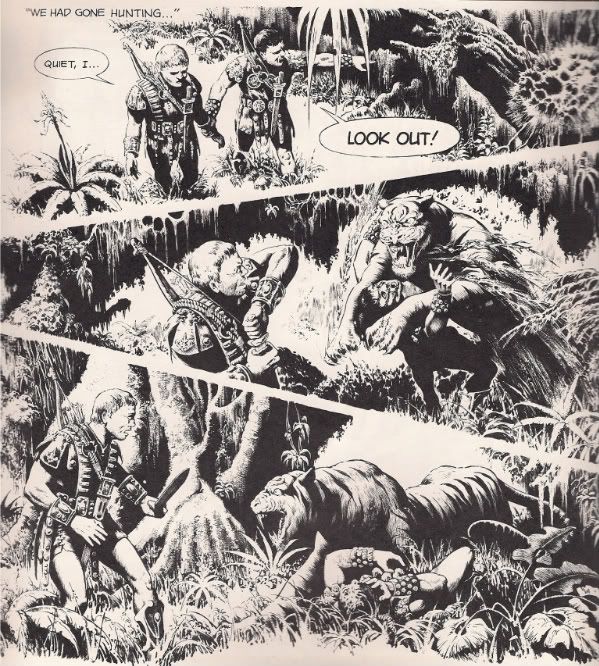

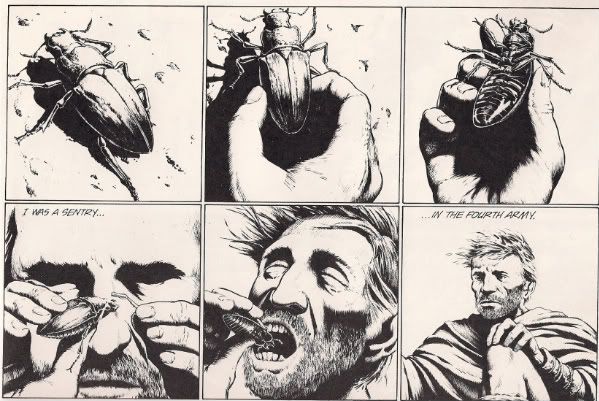

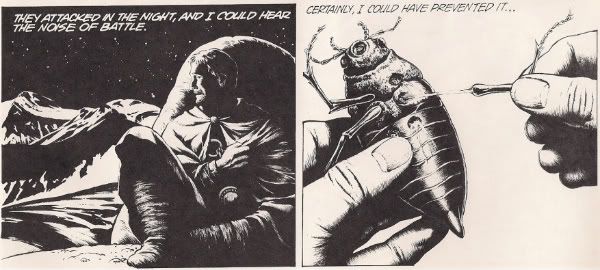

Subsequent stories proceed in much the same way: violent, material desire is thwarted by elements beyond the control of the sentry, always with a special emphasis on titanic locales. Simplistic, yes, but diabolical – there isn’t one action scene or bit of daring in this book that isn’t coated with irony or in active anticipation of the hero’s downfall. Just look at this:

Vintage newspaper serial stuff, from probably the book’s weakest tale. The encounter with the tiger leaves one brother maimed and the other scarred; the latter sets off on a journey to find an old mystery man who knows healing magic, his lair fittingly large and horrible, and filled with beasts to fight.

Our Man kicks his quota of ass, but alas – the magician’s spell causes his brother’s fingers to grow uncontrollably, and anyway he’d been captured by the magician while the hero was busy, and now his fingers will be cut off again and again for all his life, ha ha ha ha haaaa!

Still, even a story as silly as that benefits from Dionnet’s distaste for genre heroism, and especially Gal’s devotion to selling the both the occasion of the action and the constant visual metaphor of ambition dwarfed. Even one of Dionnet’s more lackadaisical plots, concerning an ambitious commander ruined by a random local boy carrying the plague, becomes somewhat straightened by Gal’s recurring motif of homes and tents as vessels for surrounding, burning death.

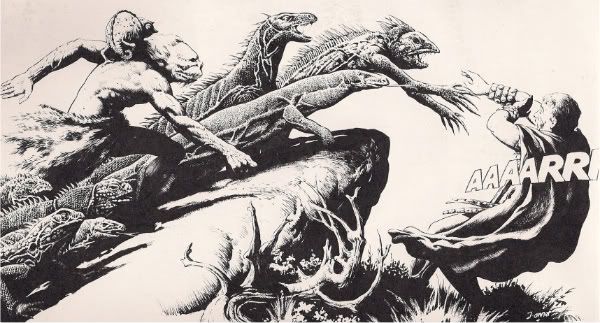

Again, though, this stuff’s probably best taken at its most visceral.

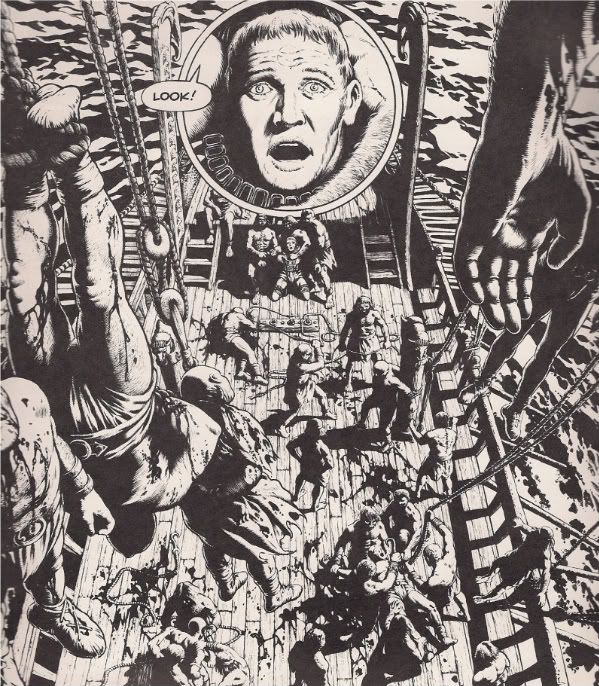

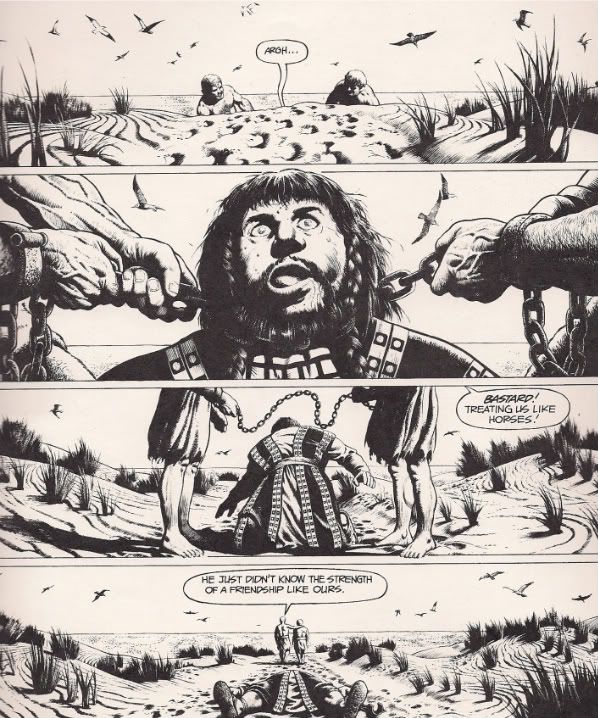

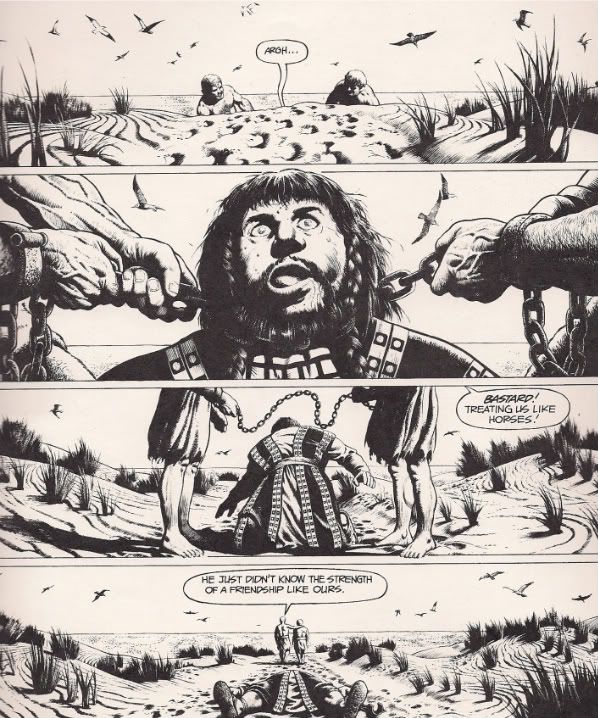

Two soldiers away from battle, one attempting to sell the other into slavery for financial gain. Whoops – the seller winds up on the same ship as his erstwhile item, and combat breaks out again. Here it’s chance that fucks pride up, the coincidences that happen in expansive spaces. Still, Dionnet has a soft spot for the enslaved, and just as a fresh army rushed in to re-take the haunted city from Story 1, a new master is again overthrown by ex-soldiers, ex-merchant & good, only equals at the bottom.

The conquest of Heavy Metal would reach its end too, and comics of this size would soon get less viable for direct English localization. You might be able to find a copy online for not too much money, though – they did seem to print a lot of these things, in the flush of early victory.

Dionnet kept working with Gal into the ’80s, with the dark fantasy albums The Vengeance of Arn (1981) and The Triumph of Arn (1988); he left his editorship with Hurlant in 1985, two years before it suspended publication. Gal later began work on a color album with writer Alejandro Jodorowsky, La passion de Diosamante, which saw publication in 1992. From what I’ve seen, color takes away from Gal’s power; the rawness of black and white underscore the power of his buildings and mountains, while color mutes it all into decoration.

He wouldn’t get the chance to refine it. Gal died in 1994, at the age of 52. The second volume of Jodorowsky’s series wouldn’t appear until 2002, drawn by artist Igor Kordey, in the very thick of New X-Men and the whole Jemas thing at Marvel. Speaking of the folly of men’s struggle.

I don’t know of any other Jean-Claude Gal books in English. There might be a story or two lurking somewhere in that Heavy Metal back catalog. I wonder how else his heavy realism became the weight of powers beyond accomplishment, sneering at mortal effort? Or did it? Comics triumph gave us this much, buried to dig up; our little resistance against obscurity’s campaign. It was all in here, from the man who saw how it worked, and delivered his urgent transmission:

Shit does happen.

Dommage qu'il ait apparemment privilégié sa carrière d'enseignant à la bédé.

Dommage qu'il ait apparemment privilégié sa carrière d'enseignant à la bédé.

. Côté scénario les mini histoires ne sont pas forcément transcendantes mais ça reste bien sympa.

. Côté scénario les mini histoires ne sont pas forcément transcendantes mais ça reste bien sympa.